- Home

- Ursula Martin

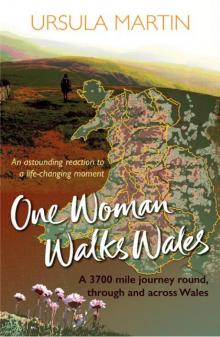

One Woman Walks Wales

One Woman Walks Wales Read online

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

FOREWORD

PROLOGUE

TWO YEARS LATER

THE SEVERN WAY

THE OFFA’S DYKE PATH

GLYNDŴR’S WAY

CONWY VALLEY

RIVER DEE

CISTERCIAN WAY

CAMBRIAN WAY

COAST TO COAST PATH SNOWDONIA TO THE GOWER

ANGLESEY AND THE LLEYN PENINSULA

OWEN’S ACCIDENT

THE MARY JONES WALK

THE DYFI VALLEY WAY

CEREDIGION AND PEMBROKESHIRE COASTAL PATH

THE RIVERS TWYI AND TEIFI

WALES COASTAL PATH FROM CARDIGAN TO CARDIFF

RIVERS TAFF AND USK AND WALES COASTAL PATH TO BRISTOL

WYE VALLEY WALK

EPILOGUE

FINAL WORDS

Author’s Note

ABOUT HONNO

Copyright

ONE WOMAN WALKS WALES

by Ursula Martin

HONNO PRESS

Owen; I’m glad you’re alive

FOREWORD

It is a great privilege to be asked to preface the story of such a personal journey of self-discovery. Ursula Martin’s determination in the face of a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, and subsequent decision to walk many thousands of miles across Wales and tell as many people as she could about the symptoms of ovarian cancer, are incredible. I am in no doubt that Ursula’s journey has helped a huge number of people to learn more about this disease and the work we must do to make sure women have the best chances of survival – every one of the 25,000 women living with ovarian cancer in the UK, and those diagnosed in the future.

Ovarian cancer can be devastating. One woman is diagnosed with ovarian cancer every day in Wales, and all too many die every year from the disease. Target Ovarian Cancer is the UK’s leading ovarian cancer charity. We work to improve early diagnosis, we fund life-saving research and we provide much-needed support to women with ovarian cancer, across all four nations of the UK.

It is for women like Ursula that we exist. Her strength and determination know no bounds, and we are profoundly grateful to be a small part of her story.

Annwen Jones

Chief Executive, Target Ovarian Cancer

PROLOGUE

It started with a sharp pain, deep down in my side. A period pain, except I wasn’t bleeding; I hadn’t had periods for a few months. The recent extreme physical exertion I had put my body through meant it had stopped bleeding to conserve energy. It felt like a period pain except it was in the wrong place: too far to the right, almost at the top of my hip bone.

Late at night in a crumbling house in a small still village, remote in the brown plains of north-east Bulgaria, I lay on my sofa-bed rubbing my right hip and deep into my belly. There was a bulge there. A bubble of sensation slid into the centre of me as I pressed my fingers deeper. I didn’t think this was a sign of something badly wrong, just strange; I had never noticed before that my body did this. I couldn’t lie on my stomach, there was an uncomfortable pressure in there; but still I didn’t realise there was anything really wrong

There was something pushing against my intestines, taking all the space. But I didn’t know it was there. There was no conscious alarm, no clanging alert-signals or heart-fluttering realisation.

I hitchhiked back to the UK for Christmas. Borrowing a pair of Mum’s jeans for a family gathering, I crowed about fitting into a size 12. I was the fittest I’d ever been. I’d just finished a three-month kayak journey, covering 1710 miles through seven European countries. I was bronzed golden-brown with blonde streaks in my curls of river-washed hair, and the technicolour memories had made my eyes blaze bright. As I swung in the motion of constant, economical paddle-movement, the kayaking had changed my body. Hours and hours, day after day I forced the bulbous plastic shell forward against oncoming winds and river conditions. I was full of muscle, my stomach lifted and flattened, my arms and shoulders strong and solid. Even my legs lost fat through daily pushing against the kayak body. I was healthy and beautiful. I was the most confident I had ever been. But there was a pain in my stomach and I didn’t recognise it. I couldn’t sit comfortably in a chair, there was something inside me that stopped me folding, made a bloated unpleasant pressure in my belly.

The family Christmas became New Year’s Eve with friends in Bristol. I mentioned my strangeness to a few people. I feel like I can’t bend, I said, blithely. Go to the doctor, they said, so I did, making an appointment as a temporary patient at the surgery around the corner. I was only passing through.

The doctor raised an eyebrow, said it was probably a large ovarian cyst, and sent me for a scan, to confirm it.

I was referred to a consultant who told me that I needed surgery, and scheduled it for twelve weeks’ time. Then a blood test showed the cyst might actually be a tumour, that there might be a huge tumour inside me. I was bumped up the list, suddenly a priority. They’d used the word tumour and I had to ask, is that cancer? I’d attended the appointment alone, and a rise of tears grew up within me, my face scrunching in sudden emotion as the implications of that word sank in, becoming the clichéd trauma and all that suggested. There was a heaviness in that word, with all its implied suffering, finality and death. The consultant and nurse bent forward, patting a knee each as if choreographed; they’d been waiting for the ramifications to percolate through me.

I found myself waiting, my fluttering free life unexpectedly stilled by blooming uncertainty, waiting for the next appointment, waiting for another blood test, a scan, a pre-op assessment. I was waiting for a definition that never arrived, the name of the thing inside me, whether or not it was going to kill me. My stomach grew and grew. I couldn’t shit, couldn’t bend, couldn’t tighten my clothes. My ovary was pressing against my diaphragm. There was fluid in my lungs. I couldn’t breathe at night. My stomach distended. I felt the growth sloshing as I walked. It loomed silently, motives unreadable, like a jellyfish going about its unfathomable business, sculling slowly through the ocean. I reduced my gait to a gentle shuffle, careful to avoid shaking the bag of matter inside me.

I couldn’t forget this was happening. Pain would cut through my belly, the cyst illuminating from within, a thundercloud flashing in sudden booms of white.

“If it bursts before the op, don’t go to A&E,” said the consultant. “Come straight to ward 78.”

“How will I know if it bursts?” I said.

She looked at me sharply, assessing my naivety. “It will hurt.”

I lay in bed and pressed my fingers against my swollen stomach. Something was growing inside me, the way a baby should. But it wasn’t a child, it was a blank-eyed, brooding, poisonous thing: a growth of malicious and murderous intent, a malignancy. I decided it was an alien baby; I’d been abducted and probed, landing back to earth with a blank memory and a mystery growth that would burst open to reveal a pterodactyl, flapping and cawing before falling to ashes, killed in the bright light of the operating table.

Six weeks after the first doctor’s visit, the operation date arrived. February 14th 2012. I joked about the date with the nurse in false, forced brightness, as I sat waiting for the needle that would put me to sleep. When I woke up, there was only pain and heaviness. I didn’t know where my body was. I saw the ceiling, beige tiles full of holes, and felt a sense of busyness around me, machines beeping and people moving quickly, intently.

The muscles of my stomach began to ripple, then exploded into bursts of pain.

I was nothing but pain. My breathing stopped. My newly opened body was pulsing against its closure, raw edges stitched together moments previously were being pulled apart by involuntary muscle twitches.

The wound screamed and I lay paralysed. I was caged by pain. I was the colour red. I was clay inside a fist.

The nurse found me lying there, immobile, my breathing caught at my throat. She looked into me and held me in her gaze. She was a tall, beautiful woman. I was a flat, heavy line of hurt.

The surgeon bent towards me and told me that as well as completely removing the right ovary, they had also scooped out a growth from my left ovary. In this knowledge came a flash of my future: chemotherapy, spreading cancer, no children. Infertility, hormone imbalance. I was a pair of listening eyes attached to a two-dimensional flat plane. I knew that she was telling me this to check my comprehension, to check that I was present.

My body was assessed for signs of internal bleeding, and the nurse rolled me to one side to administer a powerful painkiller. As she eased me down it came again, the paralysing red roar, but this time she was there, at my face, above me. The pain was dragging me inside myself but she told me to look into her eyes. I held onto her eyes; they were beams of light, a rope to cling to that pulled me out of my pain cage. She told me to breathe, I did and the pain receded. I smiled, and she smiled with me, we were together in that moment.

They took me to the organised murmur of a hospital ward. People muted by illness, curtailed to quietness. Intimacies conducted in full view, unspeakable acts removed behind curtains, privacy maintained through averted eyes.

Morphine dazed me, gave voices a cathedral-like echo, brought them from the other side of my room to speak at my bedside, awareness advancing and retreating at each blink of my eyelids. There were only pillows of sleep and the catching of shallow breaths that first night, my alarms beeping, bringing the nurse over to check I was alive. My body wasn’t moving, it felt pressed down, muted, made heavy and quiet by a chemical cosh, lungs barely sipping at air. I was marooned in the night, eyes beaming out from my island bed.

They got me out of bed the day after the operation, body consumed by a fire at the centre, an awkward, hunched step to a chair where I sat for an hour, clicking at the morphine button, feeling my guts burn as they flopped against the raw sutures.

The first walks were to the toilet, struggling, stumbling stiff- legged, bowed at the waist with a hand supporting my stomach. I felt that if I let it hold its weight my belly would drop and burst open, spooling and spattering my insides down, out of the bottom of my gown and onto the mopped and trodden hospital floor. I was surrounded by shuffling patients, our reasons for being there bunched clumsily under the umbrella term “women’s problems”. At dinnertime an awkwardness of women would make their way down, carefully, gingerly, to the canteen, to be served an awful meal. We were looming, stumbling ghosts in long pale gowns.

A week after the surgery I was out of hospital and waiting for a diagnosis: shuffling around the house, sleeping, doing jigsaws. I had to keep my mind occupied without straining my body. I passed my birthday with my mum, watching films in a miserable hunch on the sofa, trying not to talk or think about how this was the worst birthday ever.

Time held me in a limbo of pre-diagnosis, cancer not confirmed. A week turned to two, my tumour embottled, the spooky floating potato sent to a specialist for another opinion. I was waiting for the hospital to tell me what they took out of me, waiting and suffering while they decided whether this hostile takeover was a cancer, checking what the growth on my other ovary was, whether cancer had spread, what stage of life limitation this infestation had been caught at.

I wrote postcards to friends; sending them was a way to leave the house. I aimed for the postbox, a scant 100m. Out of the house; turn left, pass three lampposts, cross the road and walk to the other side of the bus-shelter. I kissed the cards as I posted them, sending pieces of myself out into the world, small greetings soaring out beyond my agonised, reduced reach. On my way back I looked up and saw cherry blossom, pink and delicate against the pale blue winter sky. I breathed a fresh breath and remembered that the world was still there outside my personal agony. The season was turning and things were growing. It was only my life in flux, everything else remained the same. I realised how totally inward-looking I was, so focused on my own pain that I’d blocked out other sensory input. It didn’t last long, but for a few seconds I came out of myself, admired the colours and breathed the clear air of coming spring before shuffling back to the house.

I was in shock, unexpectedly vulnerable. My world was based on freedom and vitality, facing the unknown and living with vigour, flitting between different exciting events, hitchhiking, travelling abroad. Now something unexpected had happened and it was awful, beyond the scope of my capabilities. Mentally I closed down. I’d learned to be spontaneous but I couldn’t handle this. I’d deliberately removed from my life all the things I would need to cope with a serious, unexpected illness – regular income, community, home address, proximity to friends and family.

I was a nulled, dulled, traumatised person, miserable and weepy. I didn’t know what was happening, just let it come. It was too huge and frightening to even work out how I felt, I just shut down and existed. It was never OK, I never coped, just lived through it until the trauma lessened.

Eventually the results came, after scans, blood tests, second opinions and weeks of waiting.

“Mucinous adenocarcinoma.”

My right ovary had become a tumour.

“However, the growth we removed from your left ovary was a benign cyst, there’s no evidence of cancer anywhere else in your body; we believe it hasn’t spread.”

No further treatment.

“Come back for a check-up in three months. You’re free to go.”

I was diagnosed with ovarian cancer, stage 1a. I had just turned 32.

TWO YEARS LATER

What do you dream about the night before starting a 3300 mile walk? You don’t, because you barely sleep. There’s a car to scrap, a flat to clean and a rucksack to pack. There are emails to send, a Facebook page to update, press coverage to arrange and donations to solicit. If you did dream, it would be of lists, of frantically scribbling down jobs in a small white notebook, each one an attempt to capture the fear-whipped frenzy of a thought whirlwind on paper, make it tamed and tangible.

Publish website

Add Glyndŵr’s Way

Business card

Mail redirection

Preliminary route plan

Download route maps

Suma – apricots, Bombay mix, dried veg, peanuts, sultanas, muesli

Scan ID

Things to buy – boots, rucksack, sleeping bag, mat, keyboard, socks, hand-warmer, bivvy bag, multi-vits, first aid kit

Phone BT

Phone council

Tax form

Buy one more mid-layer top

Type up press release…

You definitely don’t think, dream or imagine what it’s like to embark on a 3300-mile walk, because that’s impossible. Unimaginable. You don’t dream about tumbling down tired to watch clouds move large on the wind, of 500 sunsets seen from a sleeping bag, about the perfectly-balanced colouring of green fields, blue sky, white clouds, the delicacy of infinitesimal moss forests, the tingling swish of immersing dirty hair and face into the rarely realised treasure of a hot bath.

You don’t dream about the pain of a 3300-mile walk; because you have no idea of how much it will hurt.

The reality of a 3300-mile walk is an idea too big to fully comprehend in its amorphous whole, so it must be broken down into component parts and dealt with that way. I knew that I could do this, I’d done it before. I could walk and camp, I could carry my things on my back, find sleeping spots, live with hardship. I could pack an assortment of clothes, kit and dried food into a thickly-strapped pack and leave. That knowledge was enough.

I was panicking, packing up my life, leaving my new-found home behind, heading out to travel. Was I strong enough, could I do this? I’d arrived in Machynlleth weak from cancer, in need of many things: of a home, of strength, of care and of support, of community. I found it all

there, nurtured myself and grew strong again; I was strong enough to leave but it was frightening. I was out there when I fell ill, out there with nothing when I became weaker than I had ever been before. Was I really doing this again? Was I really leaving everything?

I’d gone travelling five years earlier, packing up my belongings in a huge Victorian room near the sea at Aberystwyth, leaving a job in a homeless shelter and becoming a hobo myself. I’d left to release my tightly wound self, let go of plans, expectations, definitions of self, let go of self-imposed restrictions. I wanted to learn to allow myself to just live, to simply exist, learning to cope at the uncertain edge, where safety met danger, where the spice of life lived.

Two years of journeying had begun with baby steps, volunteering on Welsh farms, and branched out into hitchhiking, beach-living and Spanish festivals, doing small jobs here and there to top up my carefully hoarded bank balance. I’d reached a life of freedom and spontaneity, kayaking the length of the Danube before living in Bulgaria for the winter, planning a walk back to Britain. However, with the surprise discovery of the tumour everything had changed. I’d been ripped away from a housesit in Bulgaria, all my belongings left neat and tidy for a two-week UK Christmas holiday that I didn’t return from.

I was 32 years old and I’d come through a small but significant cancer. I had no job, no money, no husband and no children; just a slowly healing abdominal wound, a tearful and traumatised psyche, a group of friends in the Dyfi valley and no real idea of what to do next. Shipwrecked by a sudden storm of illness, a wave of cancer had washed over me and deposited me high up in the Uwchygarreg valley, shaken and discombobulated. The immediate danger had passed and there was only had a small chance of the cancer returning. But it had changed my life: my sense of strength and surety had gone, both in my body’s reliability and of my place in the world. It took months to heal, to find myself again and remember that I was strong and free.

Walking 400 miles down the River Severn and back up the Wye six months after surgery had been part of that return to self. It had been a healing journey, a reminder that although this attack on my life had happened, although I’d been left weakened, I was still myself. I could still shoulder a bag and leave safety, go out and cope in the unknown.

One Woman Walks Wales

One Woman Walks Wales