- Home

- Ursula Martin

One Woman Walks Wales Page 2

One Woman Walks Wales Read online

Page 2

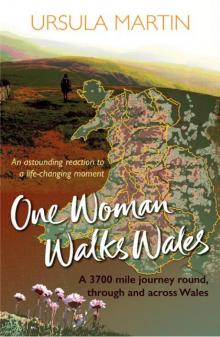

I’d looked at a map and seen that the Severn started a few miles from my house. I could follow it all the way to Bristol, the city of my illness and treatment, the place I had to keep returning to for check-ups – regular scans and blood tests to see that the insidious sneak had not returned. That’s what started the whole thing, going into follow-up treatment, facing a five-year schedule of appointments; I thought, I know, I’ll walk to hospital, that will make an unpleasant and restrictive experience more bearable. From that idea this adventure grew and grew.

I planned a second walk, a public one this time: fundraising for charity. I’d loop down the Severn to Bristol in time for a hospital check-up, but this time I wouldn’t head home. I would go up the Offa’s Dyke Path and around the Wales Coastal Path back to Bristol in time for another appointment six months later.

But this didn’t seem enough to fill the time. I added in the Glyndŵr’s Way, an easy detour connecting at either end to Offa’s Dyke. I’d been inspired by the proximity of the sources of the Severn and Wye and kept seeing pairs of rivers where I could trace my way up from the coast to the source, then walk a couple of miles to another source and down to the sea again somewhere completely different. I kept seeing paths that would slot nicely into my route: from Conwy to Cardiff via the mountainous Cambrian Way, then back to Conwy again via the Coast to Coast Path. Each piece of walking seemed essential: how could I walk Wales without covering the mountains or the coast? It was a surprise when I totted up the total and found that added together all these paths made up a 3300 mile walk.

8 months, two hospital appointments, 3300 miles. Or so I thought.

Now, on 2nd March 2014, two years after my illness, I was on the way to find the source of the Severn for the second time, fixated on a single idea: walking to hospital and telling people about the symptoms of ovarian cancer.

Survival rates for the disease were low. Wales was the only UK nation not to have paid for a national awareness-raising campaign; it also had the lowest UK survival rate (back in 2012): three per cent lower than England after the first year. At the time almost two-thirds of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer were dead within five years. Women were dying from ovarian cancer because they didn’t know they had it until it was far too late to cure, and treatment was palliative rather than curative.

The ovarian cancer charity told me it was a sign of late diagnosis. I could change this by trying to encourage the Welsh government to mount a campaign, but I could also change it on a smaller scale by talking to as many people as possible.

In the aftermath of my serious illness I felt a need to Do Something. Ovarian cancer had claimed me, become my cause. The shock I felt that a tumour could grow inside me without my knowledge, almost guilt that I hadn’t known, hadn’t noticed what was happening to me, turned to a drive to make this experience different for other women. I felt that I could make a journey to tell women in Wales about the symptoms, which fitted in perfectly with my self-centred need to travel.

I had help from Target Ovarian Cancer during my illness, an information pack in the post and a poster in the hospital. I looked at the three ovarian cancer charities and it seemed that Target was a charity that campaigned for increased symptoms awareness at government level. I decided to fundraise for them and they were incredibly supportive throughout my journey.

I visited the Penny Brohn Cancer Care centre twice during my illness; they were an invaluable source of help, advice and support. I attended two of their residential courses for free and it’s where I learned how to begin to cope with a cancer diagnosis. I felt I had to support them in return, to help provide free treatment for those who came after me.

I signed up for Facebook and Twitter during this time (Instagram felt like an app too far). I’d never used these things before, rejecting their inauthenticity, their disconnect from real human interaction. But these websites turned out to be invaluable for communicating my story to people – people who learned more about ovarian cancer from me, people who offered me beds, people who made donations and people who offered constant, uplifting, online support in response to my photos and updates.

If I talked about ovarian cancer on Twitter and Facebook, made a journey that got people’s attention, got my posts shared, got my story into local newspapers and radio, if I scattered as many symptoms-information cards to the winds as I could, then that important info might nestle into the back of the right person’s mind. Perhaps there would come a day when they were looking at themselves critically in the mirror, realising they’d felt bloated and heavy for a long time, or maybe they’d be talking to someone about a recurring pain in their pelvis, and my information, that dog-eared business card they’d found in a café, would form part of the critical mass that led to them making a doctor’s appointment. That was the best I could hope for; this wasn’t a journey which would save the lives of thousands of women, but it might increase the chances that ovarian cancer was caught earlier for the 350 women in Wales diagnosed with it every year.

Adrenaline had me bleary but alert at 6am after just a few scant hours of sleep. I’d named the day months ago and now it was here; it was finally time to pack the last pieces into my rucksack, throw it on and make my way down to Machynlleth where there would – hopefully – be a group of people waiting to wave me off. I was a plump, unpractised woman in a raincoat and woollen hat; the only thing creating their belief in me was the fact that I was stating I would do this walk. I had no idea if I could, mainly because I had no idea what I was actually attempting.

I’d given myself a rough target of ten miles a day for the first few weeks, seeing it as a kind of on-the-job training. If I walked less than ten one day, I’d make it up the next. In my planning I’d imagined ten miles a day for the first month, fifteen miles a day for the next months and that left nineteen point six miles a day if I was going to complete my walk in the time I’d set for it, to fit into the six-month schedule of hospital appointments which had prompted the initial idea. Yes, you read that right. I actually planned this walk by making a list of all the paths I wanted to walk and then dividing that by the number of days between hospital appointments, and then nodding. Yes, I can walk twenty miles a day. What was I thinking?

I’d left no time to train for this monster challenge, focusing instead on working to earn money to live on as I travelled. A year of illness and living on benefits had reduced my savings to zero. I worked as hard as possible as a home carer, always making myself available for shifts and spending weeks at a time in the homes of dementia sufferers.

I gained fat, not muscle. My body was used to sitting in a car; the most effort I expended was getting down to the floor to towel dry elderly feet. But after buying kit and making preparations, I started with a fund of several thousand pounds. It was enough, as long as I was careful. I intended to live on £5 a day, finding dried food that I could carry and eat easily. I decided not to take a stove, trying to reduce weight and dirt in my bag. Couscous became a staple food, something I could rehydrate with cold water. Couscous and various vegetables and, eventually, tinned mackerel. My £5 budget was hard to stick to but I kept it there, the mental limit meaning I overspent up to £10 by sneaking occasional toast or chips in cafés, rather than going as far as spending £15 or £20 on whole meals.

My flat was bare but not bare enough. All the tiny pieces of my life needed to be attended to, tidied up, put somewhere. I’d almost made it. My flat cleaned and arranged, rucksack neat and jammed full, extra supplies stored at my friend Ruth’s. Annie came to pick me up and drive us the four miles down to the clock tower, the monument that sits at the centre of Machynlleth, the gathering point where I’d decided to say goodbye.

“I’ve got this”, I said to Annie when she arrived to collect me, waving a Welsh flag I’d picked out from the back of a drawer. “But I’m not sure where to put it.”

“How about on the end of here,” she said, plucking a length of bamboo from the stack in the still-untidy porch. And that’s how my walk

ing-pole was born, the first of a pair that I’d take the full distance, grinding them down so that they were significantly shorter by the end of the walk.

At the clock tower was a small group of my friends. We hugged and took pictures, not quite sure of what to do. Anna came with her three robust boys, playing chase around the legs of the Victorian monument. Heloise came ready to walk out of town with me, Ruth and Naps came to the edge of the golf course. We led a small procession down the centre of the road, the local news photographer catching people smiling and waving behind me.

It was exciting, not sad; my friends were used to saying goodbye to me.

THE SEVERN WAY

Route description: The Severn Way traces Britain’s longest river from source to sea. Starting in the wild uplands of Plynlimon it descends to the agricultural valleys of mid-Wales before widening and meandering through the floodplain of Shropshire and down to Worcester where it becomes tidal and huge. It ends under the two vast Severn bridges, where the estuary is almost four miles wide.

Length: 223.9 miles

Total ascent: 3,280m

Maximum height: 605m

Dates: 2 – 23 March 2014

Time taken: 22 days

Nights camping/nights hosted: 4/18

Days off: 1

Average miles per day: 10.67

The route away from Machynlleth towards the source of the Severn at Plynlimon led me up a single-track road, the houses falling away as I rose higher into the hills, ascending the Uwchygarreg valley. Eventually I would pass Talbontdrain, the house I’d been lucky enough to rent a part of: the wonderful place where I’d recovered from illness and then used as a dormitory as I worked all hours in walk preparation. Knowing I wouldn’t see my neighbours again for months I detoured down the rocky track, through the trickling stream and up again to their secluded cottage, where I sat in their steamy kitchen to drink strong coffee.

They came out to walk along with me, my lovely friends – the baby strapped up against James’ belly, Vicky taking photographs. We had a meander further along my path until the road ran out and turned into forestry track which started to climb, winding upwards through cleared plantation. As we said goodbye, hugs for luck, eating final pieces of cake, it started to rain – lightly at first, but as I trudged upwards, along the side of the valley, it became heavier. I had no idea this was coming; in the whirl and kerfuffle of preparation I hadn’t even checked the weather-forecast. I’d taken my waterproof off and, after a while of trying to ignore the rain, decided it would be a better idea to stop and put it back on again.

The rain became heavier still as I stood in the faint shelter given by the thin line of trees at the edge of the beaten-stone track. They were wrongly aligned to keep the rain off me and it beat in, breezing and misting against my legs. I fumbled my rucksack-cover out of its zip pocket, but there was a concertina-like sleeping mat strapped to the back of my pack and the cover wouldn’t stretch over it. I pulled and tugged at the inadequate cover until I’d centred it as best I could; the sides of my bag were still exposed but I decided that was good enough. I also decided not to put my waterproof trousers on. I couldn’t be bothered with the faff of removing boots and balancing myself, the trousers felt clumsy and awkward.

I walked on, still following the forestry track, beaten yellow stone bleeding into rough muddy edges where ripped branches and churned earth marked the passage of huge, heavy machinery. It took another couple of hours to climb up to where the quiet ranks of pine forest met the grasses of Hyddgen. This was the open land that led towards the lump of Plynlimon, an amorphous overgrown hill that just squeezed, tip-toe, into the name of mountain.

I saw the mountain ahead, checked the time and noticed oncoming dark, way sooner than I’d expected. The friends, stop-offs and chats had been wonderful, but cost me time. I’d have to sleep on the mountain, or the moorlands this side of it, rather than in the woods on the other side, as I’d anticipated. This was an exposed and grassy kind of a place: no overhangs or clefts of rock, just wide open expanses of soggy grass and bog, waterlogged, wind rippled. No place to sleep.

Because I’d planned to wild camp, I didn’t have a tent: just a tarpaulin to put underneath me to keep the wetness from soaking upwards and a bivvy bag to wriggle into as a damp-proof outer layer. It wasn’t full preparation for all conditions, more a deliberate/calculated absence of planning. I’d always preferred to be under- rather than over-prepared, to allow for chance to aid as much as hinder. I hated the fussiness of ‘what ifs’, the overburdening of a bag full of objects for ‘just in case’; it felt like using possessions to control fear of the unknown. In my frantic planning I’d tried to err towards the minimum of what I might need, sensing that I’d chop and change along the way, learning my true needs during the journey itself.

I’d learned this eighteen months previously, during my first long walk along the length of a river in Galicia, northern Spain. I’d hugely weighed myself down, leaving the UK with twenty-six kilos of suitcase and rucksack, carrying the gift of a lined army-issue winter overcoat, to use once I reached the colder winters of eastern Europe. How ridiculous to think that I couldn’t buy a coat once I went further east. I’d travelled in this way, slow and over-weighted, for over six months, but once I started walking it became immediately apparent that I was physically incapable of walking long distances under so much strain. I remember finding a large, open-mouthed swing-top bin in the woods, and depositing eight vests, draping them over the edge for someone else to pick up. Why did I think I’d need eight vests?

Here in Wales I wasn’t carrying any vests. I could feel the cold of my rain-soaked clothes as they clung against my skin, only the warmth of my efforts in climbing the stone track kept me from shivering.

Across the open grasses was a flatland where streams meandered, leading over towards where the mountain began to rise. This was where the Rheidol started, the river that ran its swiftest course towards the sea at Aberystwyth. Up there, on the slopes, began the trickling of the Severn and the Wye that I’d decided would be the beginning and end of the entire 3300-mile route. They ran away down the other side of this heap of rock and earth – one going north, the other south, heading out on their meandering routes to the sea, meeting again at the mouth of the Bristol Channel to mingle into the ocean. I’d walk away on one and home on the other, with all the other routes I’d planned in between. But first I needed to sleep somewhere; a storm was on the way and I decided not to chance it. There was one place of shelter – the sheep barns of Hyddgen, the only building in the entire landscape, away to my right.

I splashed into a puddle as I stumbled over the rock bridge leading to the barn, and my feet were instantly soaked. I didn’t understand what I would months later, what months of wet walking would teach me, that without waterproof trousers the rain had run down into my boots and saturated them from the inside out.

Clambering over the puzzle of gates that enclosed the entrance to the barn, I saw an expanse of beaten-shit floor, separated into four pens. I walked down the row, searching for the pen that had the least damp patches, settling for the end one, closest to the mountain. I laid my tarpaulin on the ground and my sleeping-kit out on top of it, carefully trying not to let anything touch the sheep-shit. I searched further down into my bag for fresh clothing and pulled out wet clothes. The rain had leaked around the sides of the raincover into my rucksack. Oh damn, first day out and I was already fucking up. I didn’t want to change my wet clothes for rucksack damp ones, again eschewing the awkward, uncomfortable fumbling. I felt dazed after four hours in the rain and just wanted to lie down. I got into my sleeping-bag and pulled it up around my head, and just lay there, staring. After a while I remembered my handwarmer: powered by lighter fluid, the perfect small heat source. I pulled myself out of my sleeping bag, shuddering in the cold air and fumbled it together, scraping the matches to start it.

I lay in my sleeping-bag, shivering in shock and stared at nothing, too worn out

to move, too tense to sleep, listening to the rain rattling against the barn roof. The strong wind blowing water at me for the previous four hours had left me blasted, in stasis. I swapped the handwarmer from place to place, trying to warm my body. I was cold and seemed to be taking an age to warm up. My feet were solid cold, covered in slimy wet socks, damp with the water that had trickled down into my boots, I was too ignorant to take the socks off and let the dry sleeping-bag warm up. It was hard in the triple cocoon of sleeping-bag, liner and bivvy outer layer to get my hands down lower than my waist but I wriggled around, trying to place the handwarmer against every part of me in turn. It was a cold and wakeful night. The wind roared and whirled against the tin roof of the barn, I heard it bashing and blowing all night as I surfaced from my semi-sleep to change the position of my little heat bundle. I never really got any part of myself warm enough to slide into deep sleep, always having to keep moving the heat source round to the parts of me that were numb with cold.

I imagined myself out there, on the side of the wet, grassy mountain, nothing to string a tarp to for shelter against the rain and hail, and I was glad I’d come inside early. Not pressing ahead to camp in the dark later on was the right decision. If I’d carried on and tried to get as far as I could that day I would have been on the side of an exposed mountain in a rainstorm, close to freezing, with no tent. Disaster.

When shit got rough, when I was wet and tired, I made a decision that kept me safe. It was a good thing that I could do this, ill-equipped and unfit as I was. I was able to think clearly under pressure. That was something I’d do over and over again as I kept walking: coming to the end of a day, fuzzy-headed through low blood sugar, grimy, aching, exhausted. All I’d want to do was throw my bag down and stare into space. But I’d force myself to think, to decide what was necessary to keep myself fed, rested and safe – and do it. It’s that skill, more than anything, more than the muscles in my legs, the cash in my bank account and the expensive kit on my back that made walking a total of 3700 miles possible.

One Woman Walks Wales

One Woman Walks Wales